BP Oil Spill Part I – Deepwater Horizon

Nov 2010

By: Laura Crawford Williams

On August 4, 2010 the Obama Administration claimed that most of the estimated 4.9 million barrels of oil from the Deepwater Horizon disaster had been accounted for and that any remaining oil was too diluted to cause the damage everyone had once feared. I thought, “Isn’t it a bit early to assume anything?” On that same day, Jane Lubchenco of NOAA stated that scientists had accounted for all but a quarter of the spilled oil. That’s about 26 percent, more than 53 million gallons of oil. This amount is five times the size of the Exxon Valdez spill. So, where did 26 percent of the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry go?

I was born in New Orleans and most of my family still lives there. As a child, I was a diehard tomboy. I loved fishing, shrimping, and crabbing with my father and brother in the marshes and offshore waters along the Louisiana coastline. It always feels like home, no matter how long I am away. My brother owns The Big Fish Charter Company based at the Breton Sound Marina and his wife is a marine biologist for Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries. They depend on the Gulf to support their growing family. Hurricanes Katrina (Aug. 2005) and Gustav (Sept. 2008) were devastating for them. To add tragedy to injury, in November 2008 my brother lost his close friend and business partner in a car accident. Then, in April 2010, came the Deepwater Horizon disaster. My family watched breathlessly as the oil moved closer and closer to the Louisiana coastline most familiar to us. I couldn’t believe it. I wanted to see it for myself.

We were in Hopedale (Breton Sound) on our first day out. The sun was just rising as we sped through the navigation channels out into the marshes. It wasn’t long before we noticed a chemical smell. After an hour in the boat, we stopped to explore some of the nesting islands. Most prevalent were Brown Pelicans, adults and juveniles resting on boom that surrounded the islands. Hundreds were balanced along bright yelow and red curtain boom floating in choppy water. As one pelican landed or took-off, the rest were left to balance using raised wings to maintain position. It was funny to watch, reminding me of something from Finding Nemo.

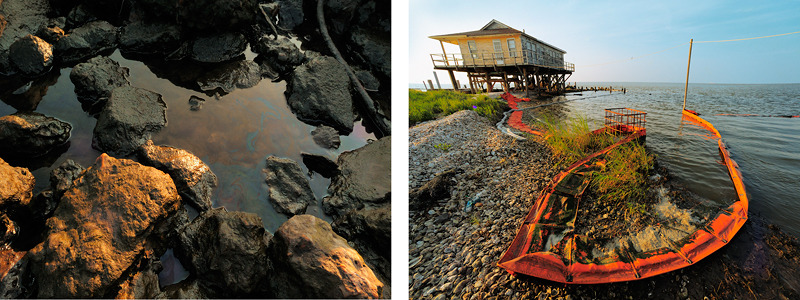

In both locations, most of the islands and marshes closest to the mainland looked good. Curtain and white sorbent boom were wrapped around islands, across bays, and along marshy shorelines everywhere. The areas closest to the mainland were well kept; boom was in place and clean. We saw an impressive number of boats in all shapes and sizes doing various, often-unidentifiable tasks. Large three-legged jack-up boats with barges and tugs attached served as offshore staging areas, providing supplies and services to the boats working farther out. The number of boats, vehicles, machinery, and people that had been mobilized since April was massive.

We saw several nesting islands off Hopedale and in Barataria Bay. Although nesting season was over, adult and juvenile Brown Pelicans were present in decent numbers and we didn’t see any birds having difficulty flying or covered with oil. Gulls, terns, skimmers, and various herons were present as well. Our boat captain in Grand Isle said, “There should be many more birds here this time of year. I guess most of them were smart enough to leave.” We heard reports over the radio about oiled Laughing Gulls, but overall the birds we saw were mostly clean. Dispersed oil was present on marsh grasses and island shorelines. A large group of Laughing Gulls stood right in the middle of it. It looked like they were wearing dark shoes at the bottom of their pale pink legs.

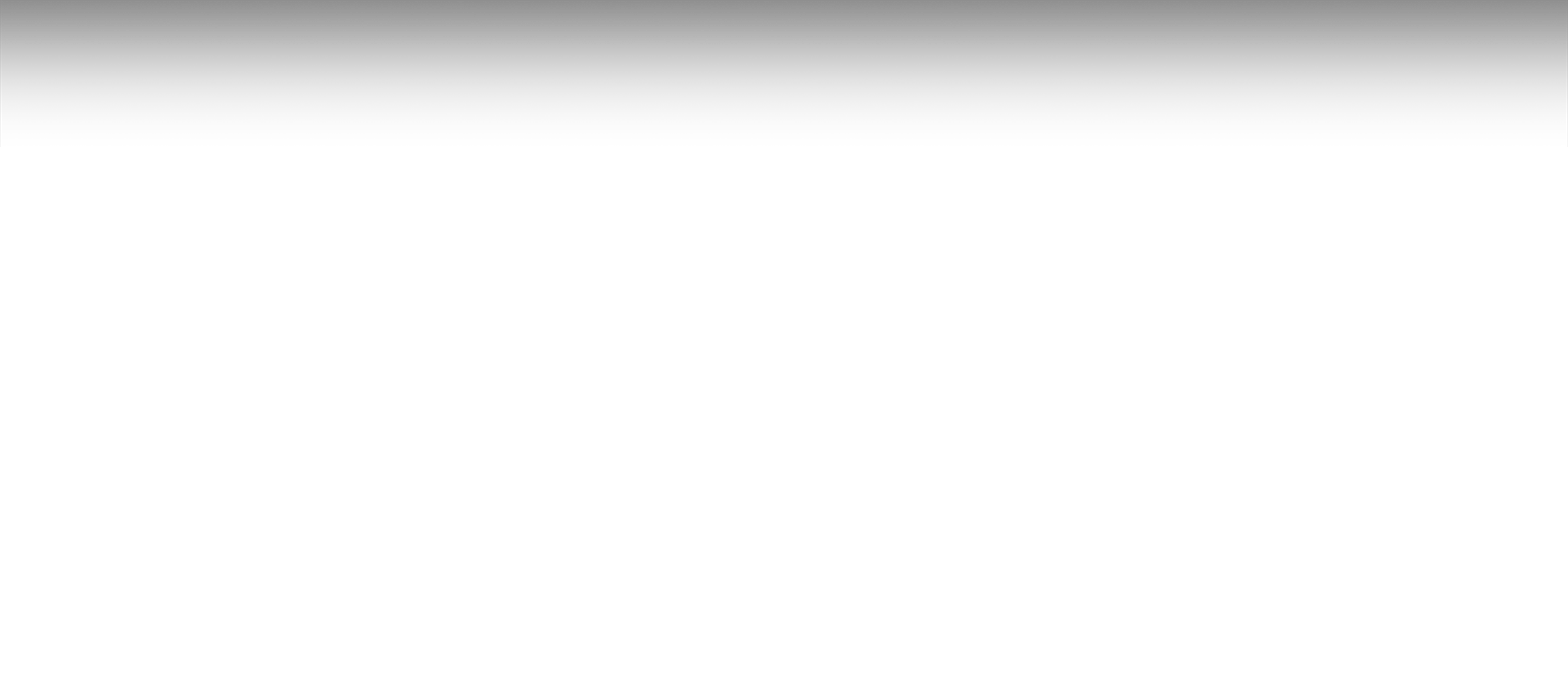

As we traveled farther from the mainland in Hopedale as well as Grand Isle, things got worse. We began seeing booms that were neglected. Many were contaminated and had drifted up on land. We saw thick black oil gathered in the crevasses of a rocky foundation supporting an old fishing camp. On island shorelines, shallow puddles were topped with a shiny iridescent substance. Sorbent boom was very contaminated, its white surface stained dark with oil. It wasn’t unusual to find large areas of marsh covered in “dispersed oil”. Up close, plants were covered in a spider web of stringy brown globs suspended in a transparent substance. People in fishing boats were marking contaminated areas with bamboo sticks topped with florescent tape. When I asked how these areas were cleaned, I was shown a vessel with a giant, mobile arm topped by a water hose. Our captain told us that heated seawater is sprayed from the hose. The heat and the pressure “wash” the wetlands creating large plums of toxic steam. The mixed run-off then drains back into the water. The same method was used in the Valdez spill, and it is blamed for much of the respiratory problems experienced by cleanup personal. Our captain described other areas where workers cleaned grasses by hand using diapers (which are then treated as hazardous materials for disposal). I don’t know what factors dictated the method of removal in each area, but the power wash and re-dispersal of contaminated water surprised me. However, I was not surprised when we routinely discovered new contamination in areas that were pristine the day before.

One of the most troubling things we discovered was a large fish kill near the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (a.k.a. MRGO). Large fish kills have been found in other areas of Louisiana and Mississippi since the oil spill began. However, fish kills can occur naturally so “officials” claim it’s difficult to confirm whether or not the spill was a contributing factor. We found dead red fish, stingrays, eel, drum, speckled trout and crabs floating along shorelines and up against curtain boom near the dam. In shallower water we could see dead fish, belly-up, all along the bottom. Gulls, terns, herons, and pelicans were feasting on the dead and dying seafood. It’s important to note that fish kills have occurred in this area in the past and have been attributed to an oxygen deficiency, possibly caused by the dam. Our captain said he’d seen kills here in the past, but never one that was as large as this.

As the weeks passed in August, the number of people and resources dedicated to the cleanup dramatically declined. Beaches were empty, equipment sat immobile, and fewer boats could be seen out in the water. This was very disturbing.